I’m a procrastinator by nature, but waiting 36 years to

publish this interview with Noam Chomsky on New Zealand’s

nuclear free policy is slack even by my standards.

My

old mate Tim Bollinger has organised an all-day event

to commemorate the 80th anniversary of the atomic bombing of

Nagasaki, on Saturday 9 August, and it seems as good a

reason as any to revisit the interview and Chomsky’s

thoughts on nuclear disarmament.

In 1987 the

Guardian Weekly ran a very brief review of the Chomsky

Reader. I’d never heard of Chomsky but the

description of him as America’s number one dissident stuck

with me.

In those pre-internet days, the mainstream

newspapers had a virtual monopoly on international news and

voices like Chomsky’s were entirely absent.

I was

working as a cub reporter on the Hawke’s Bay Herald

Tribune and the Guardian Weekly – printed on

tissue-like paper and airfreighted from the UK – was one

of the few sources of in-depth international news available

to me.

But even in the Guardian Weekly,

America’s number one dissident warranted just 200 or

so words.

I wouldn’t read anything by Chomsky himself

until the following year, when I was in Harbin, the capital

of China’s northernmost province Heilongjiang.

Advertisement – scroll to continue reading

A

Chinese American who was studying in Harbin gave me a copy

of the libertarian socialist Z Magazine which

included a 10,000 plus word feature by Chomsky

on his recent visit to Israel and the occupied

territories.

Four years previously I’d spent time in

Israel and the West Bank and had been grappling with what

I’d seen there. Chomsky helped me make sense of it like no

other writer had.

I was teaching conversational

English at the Harbin Medical University and when I

mentioned the Chomsky article to a class of medical

specialists I was surprised and delighted when one of them

not only knew who Chomsky was but said her husband was

studying linguistics with him at MIT.

She mentioned

that Chomsky was well known for making himself available to

anyone wanting to talk to him.

Six months later I put

that to the test and found myself in his MIT office

interviewing about New Zealand’s then relatively new

nuclear free policies.

On my return to New Zealand, I

attempted to interest the Dominion and NZ

Listener in running an article based on the interview

but had no luck.

A lot’s changed over the last four

decades but it’s striking how consistent, insightful,

informed and principled Chomsky’s views are.

The

interview has been edited for clarity.

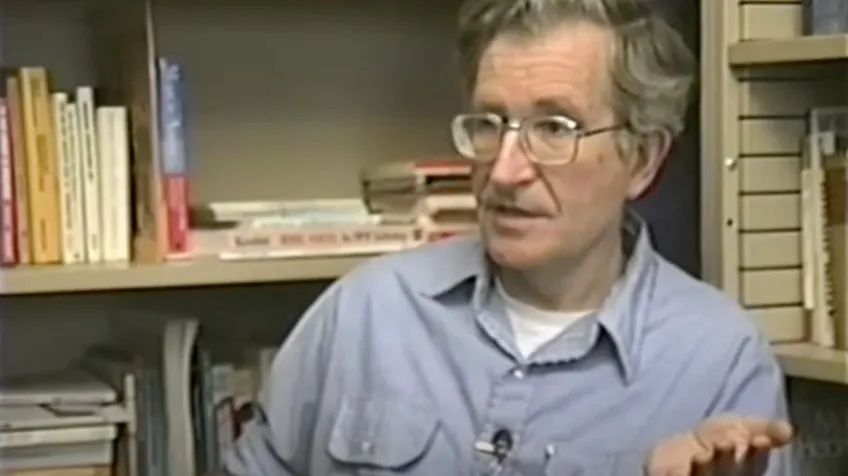

Chomsky in his MIT office in 1990. (Screen shot from YouTube

video.)

The

Unsettling Spectre of Peace

Rose: Some of those

arguing for New Zealand to remain in the ANZUS alliance say

the country could do more for nuclear disarmament inside the

alliance than outside it. Do you think that’s

realistic?

Chomsky: New Zealand plainly has a

limited range of possible options open to it. It’s a small

country; it’s not a major actor in world affairs.

But

it does have at least symbolic significance. Its stand on

nuclear issues has certainly raised the question of why we

have to rely on widespread proliferation of nuclear bases.

And that’s good, those questions should be

raised.

Whether New Zealand can raise these questions

more by being in the alliance or more by being out of it is

a kind of a technical question that I don’t think it’s easy

to give an answer to. I presume that the question’s academic

anyway because New Zealand’s going to want to stay in some

form of alliance. And the question really is, should it

press forward on its resistance to a nuclear

strategy?

Supporters of ANZUS typically argue that

the US defends democracies, preventing the spread of

communism and the so-called domino theory which they claim

could see communism spreading down into the South Pacific.

Does America defend democracies?

We have plenty of

evidence on the question of whether the United States

defends democracy. And the answer is pretty definitive,

namely support for anything that could rationally be called

democracy is an extremely low priority for American

policy.

In fact, it’s probably something that’s

generally avoided, unless we mean by democracy something

rather special. If we mean by democracy rule by business

interests, oligarchy and military linked to U.S. interests

and U.S. power, if that’s what we mean by democracy, then

yes, the United States supports democracy. If we mean by

democracy a system in which people have political rights and

people can organise and there’s access to the media and

social activism is tolerated and human rights are preserved,

if we mean any of those things by democracy, then the fact

of the matter is U.S. assistance and aid are negatively

correlated with democracy.

That’s been in fact shown

in study after study, and you can look at that region of the

world, say, take Indonesia. The United States was, like

Australia, I don’t know about New Zealand, but certainly the

United States and Australia were quite pleased at the

military coup in 1965, and with the subsequent slaughter of

hundreds of thousands of people, destroying the largest mass

popular organisation in Indonesia. The reactions to that

were qualified applause, plainly that didn’t establish

democracy.

It eliminated any conceivable basis for

democracy, and that remains the case. Indonesia remains a

very well-functioning police state behind a formal

democratic facade, and the United States and its allies are

quite pleased with that. And that’s very typical.

You

look at, say, Latin America, where U.S. influence has been

enormous. The United States has been influential in

overthrowing democratic systems, in repressing the kinds of

popular organisations that might lead to really functioning

democracy. It’s always called anti-communism, but it has

nothing to do with that.

Destroying peasant self-help

groups organised by the Catholic Church, is called

anti-communism. It’s just a name for anything you want to

destroy, and there’s just no doubt that that’s typical of

U.S. foreign policy. What’s more, it’s stated that

way.

You don’t have to just look at the historical

record, you can look at the documentary record. The United

States is a very open society, probably the most open in the

world. We have great access to internal planning

documents.

Secret documents are either leaked or

declassified relatively soon and efficiently, and we now

have a quite extensive record of secret planning documents

through the 1950s, and in fact considerably beyond, and it’s

very clear and explicit. The U.S. foreign policy at the

National Security Council over and over reiterates and

emphasises that the major threat to the United States is

what are called nationalist regimes, or sometimes

ultra-nationalist regimes, which are responsive to pressures

from the masses of the population for social reform, for

diversification of production, for independence, and so on.

It’s stated very explicitly, and those are the regimes that

must be undercut.

It doesn’t matter whether they’re

from the right or from the left or run by the military or

run by some political party that calls itself communist or

whatever. It’s all the same. If they are nationalist and

independent and are not willing to subordinate themselves to

the perceived needs of U.S. foreign policy, which means

access to resources and investment opportunities and so on,

then they have to be overthrown. Democracy has nothing to do

with it.

The freedom to rob and

exploit

It’s what you’ve referred to as the fifth

freedom, isn’t it?

It’s called the fifth freedom,

the freedom to rob and exploit, which is basically, if you

want a one-phrase description of foreign policy, which

naturally misses some nuances because it’s one phrase,

that’s about as close as you can get. The record with regard

to democracy is extremely poor.

You mentioned

Indonesia. New Zealand’s paranoia about a Russian invasion

pre-date the Russian Revolution with gun emplacements being

built in 1905. But that fear has been replaced in recent

time with a focus on Asia and in particular Indonesia has

seemed expansionist…

It’s not just seemed. It

is expansionist.

Do you think staying on

good terms with the US would help protect us against

possible Indonesian expansion, even though it seems unlikely

they’d ever go as far as New Zealand?

Indonesia

expands into third world areas which can’t fight back. No

one ever attacks someone who can fight back.

So,

Indonesia will expand into East Timor, for example, because

there they know that they can carry out a major slaughter or

something, approaching genocide, with full Western support,

which they got, in fact. Again, I don’t know about New

Zealand, but they got support from every Western power,

primarily the United States, but also its allies, right

through the worst period of the slaughter. And that they

know they can get away with, so of course they’ll do

it.

Attacking New Zealand would be a different matter.

Regardless of whether we were in an alliance. Whether New

Zealand is or is not in a formal alliance, its links to

international capital are so tight that it would be

protected against any Indonesian attack.

Are

countries that take part in military alliances with America

tacitly supporting the dictatorships of Central and South

America and Southeast Asia backed by the

US.

That’s their choice. Usually the answer, in

fact, is yes. There are some exceptions, but those are

separate choices.

Being a part of, say, NATO, does not

entail that one must support a murderous terror state in El

Salvador. In fact, it has that consequence, but that’s just

a decision of the governments in question. It’s not forced

on them by their membership in the NATO

alliance.

South Pacific Nuclear Free

Treaty

The USA, England, and France all refused to

sign the South Pacific Nuclear Free Treaty. It was a very

watered-down treaty designed specifically to get the USA and

UK to sign – France was never going to.

Why

do you think the US and UK refused to sign up to

it?

I think we have to be a little more cautious

here. This is only one of a number of cases.

For

example, the United States also refused to support a South

Atlantic zone of peace. It was the only country in that case

voting against that at the United Nations. To put what you

just said in a broader perspective, take a look at the

United Nations disarmament votes.

The most interesting

and dramatic case is in the fall of 1987, at the time of the

summit which led to the INF [Intermediate-range Nuclear

Forces] Treaty, so all attention was focused on disarmament.

Exactly at that time, the UN had a series of votes on

disarmament. There were votes on a comprehensive test ban,

on the end to development of weapons of mass destruction, on

a number of other such issues.

On some of them, the

United States was completely alone. The votes were like 154

to 1. On some of them, it picked up France, so you get votes

like 135 to 2. On a few, it also picked up England, so votes

like 140 to 3 and so on. That’s the picture

throughout.

The United States and France are committed

nuclear powers, and England just tails along behind the

United States. That’s what’s called a special relationship.

They are in the lead, not just in the South Pacific area, in

opposing moves towards relaxation of nuclear

tensions.

That has to do with their own perceived role

as global powers. There are reasons for this. There is a

sense in which the United States and its allies are

deterring the Soviet Union, but we have to understand that

sense.

If you look at the actual planning documents

and the actual course of history, and even the public

statements, you can see what the sense is. The United States

is a global power, and it maintains its dominance by a

potential threat of military force and military

intervention, which is sometimes carried out. In Vietnam,

for example, it intervened 10,000 miles away in a massive

war, a war of aggression, in fact, against South Vietnam,

which is what it really was.

Intervention globally has

been very widespread. The United States considers it to be

its right, in fact its duty, to have the potential of

intervening using military force basically almost anywhere

in the world. That means that there’s a chance of

intervention, in fact a likelihood of intervention, in areas

where the United States does not have a conventional force

advantage.

When the Soviet Union intervenes, say in

Afghanistan, Poland, Eastern Europe, Czechoslovakia, it has

an enormous conventional force advantage. It doesn’t have to

rely on a nuclear threat. But when the United States

intervenes, it often intervenes in areas where it’s at a

conventional disadvantage, and that means it has to be

extremely intimidating.

It has to intimidate any

potential enemy, so they’ll back off. And the way you’re

very intimidating is by having a nuclear threat. So, there’s

a good reason why the United States uses the threat of

nuclear force constantly.

It wants to prevent anyone

from deterring it. It wants to overcome the deterrence of

either indigenous forces, which may be able to resist a

conventional attack, or the Soviet Union. The Soviet Union

deters the United States, there’s no doubt about

that.

Over and over again, the Soviet Union has

deterred the United States. For example, even close by, the

United States carried out a long war of terrorism against

Cuba, a major terrorist attack of the 20th century, but it

did not, after the Bay of Pigs, it did not invade Cuba

directly, outright, and basically that’s because of Soviet

deterrence, which led to the missile crisis and scared

people off, and after that there was a kind of backing off

on both sides.

How do Gorbachev’s liberal reforms

fit into that?

It’s very interesting to see how

American commentators are reacting. So, for example, they

are quite publicly saying that they’re concerned about

Gorbachev’s reforms. One reason is that the alleged threat

of the Soviet Union has played a very significant mobilising

role within the United States.

Every modern industrial

society has some mechanism by which the state intervenes in

the economy. Massively, in fact. It plays the role of a

coordinator, or stimulates production, or organises exports,

or one thing or another.

And the United States,

despite all the talk of free trade, has a very powerful

state component in the economy. In fact, if you look at the

two areas of the U.S. economy that are more or less

competitive internationally, namely high technology

agriculture, capital intensive agriculture, and high-tech

industry, they’re both state subsidised. Capital intensive

agriculture has always received both protection and some

very extensive subsidy from the state, and high-tech

industry is just a spinoff of the military system.

And

in fact, it was understood from early on, about 1950, that

the U.S. economy would be able to continue to function, and

in fact, European and Japanese industrial recovery would be

possible if there was extensive stimulation at that time by

the United States, and it would have to come through the

military system. That was clearly understood early on.

It’s often called military Keynesianism.

It’s not

easy to find an alternative to that. Economists can make up

technical alternatives, but they really don’t work, because

you have to deal with the fact that the public has to be

willing to support it. It’s very costly.

And

furthermore, the state intervention has to be carried out in

a way which enhances the prerogatives of private capital and

does not interfere with those prerogatives. So, there’s all

kinds of models that economists make up that won’t work,

because they infringe on management prerogatives. On the

other hand, military spending is just a gift.

It’s

just a welfare state for the rich. Military spending means

that the taxpayer subsidises research and development, and

the taxpayer agrees to purchase any junk that’s produced.

And that’s just a gift.

Economic Keynesianism a gift

to the wealthy

It’s a gift to the wealthy and the

management corporations and so on, so naturally that’s what

they fall into. But to maintain that system, you have to

have an enemy. In fact, the Wall Street Journal the

other day had an article which the headline was something

like, “The Unsettling Spectre of Peace.”

And it

was about how we’re going to deal with this. And they say,

well, there’s some solutions, like we can move to high-tech

armaments without any soldiers, so you have all kinds of

crazy robots flying around and stuff. Of course, none of it

will work.

It doesn’t make any difference, none of

it’s supposed to work. You’ve got to make sure that there’s

something going on that allows the United States to keep its

technical edge. And this is not weapons.

I mean, look

at the history of computers, for example. It’s subsidised.

It’s a spin-off of the Pentagon and the space programme, up

until the point where they become competitive, then private

industry moves in and makes the profits.

It’s public

subsidy and private profit. Now, that’s one thing. The other

is that, as I say, the United States needs – you have to

mobilise the population behind the intervention,

too.

You can’t send half a million troops to attack

South Vietnam by simply saying, look, we don’t like what’s

going on in South Vietnam, so we’re going to attack it and

do our own regime. You can’t say that. You have to say

you’re defending it.

Hitler was defending Germany from

the Poles. And the United States was defending South Vietnam

against the South Vietnamese. And that sells in countries

like the United States and New Zealand and the Western

world.

Everybody accepts U.S. propaganda without a

second thought. Of course, it’s idiotic. I mean, the main

war was against the South Vietnamese, clearly. There were

bombing and casualty figures and so on. But we were

defending it, and ultimately, we were defending it against

the Soviet Union and China and the Sino-Soviet conspiracy to

take over the world and the same when we attack Nicaragua,

we’re defending ourselves from the Russians.

When we

attack Grenada it’s very hard to convince people that a

country of 100,000 people that has a little nutmeg is going

to conquer the United States. But if it’s an outpost of the

Soviet Union, well, I mean, you’ve got to tremble because

who knows what those guys are up to with their missiles and

terror and so on. If you lose the Soviet threat and it’s now

being lost, it’s going to be very hard to mobilise the

population for intervention.

In fact, that’s a large

part of the reason why all this hysteria is being concocted

about drugs. Drugs is a problem, but sending arms to

Colombia has nothing to do with the drug problem. In fact,

it’s probably going to exacerbate it because the Colombian

military is doubtless involved with the

narco-traffic.

Well, it’s all obvious, but it’s a way

of building up hysteria in the country. You’re here now, so

you just read the newspapers and look at television. All you

see is, boy, we’ve got to fight this war against

drugs.

It’s what they tried to do with international

terrorism a couple of years ago.

But over the long

term, these things don’t work very well. People sooner or

later are going to begin to see that the drug problem is the

destruction of the inner cities.

My neighbourhood

isn’t being destroyed by drugs. The inner city is. And it’s

not because the Colombians.

And sooner or later,

people will realise that. And that technique of mobilisation

isn’t going to work. And with the loss of the Soviet threat,

or at least the decline of the Soviet threat, they’re trying

to keep it up because it’s going to be serious.

That’s

why there’s concern. On the other hand, there’s a feeling

that it’s to the good because the Soviet deterrent is

declining. And that’s said very openly.

So, for

example, it’s very openly stated in editorials, in the

Washington Post, in the op-eds, in the New York

Times, and so on, that we have to test to see whether

Gorbachev is serious by seeing if he allows us a free hand

in Central America. So, if Gorbachev continues to support

the Nicaraguans in their attempt to defend themselves

against our attack, that shows he’s not serious. Because

that poses certain limits on our attack.

As far as

nuclear weapons are concerned you can understand why a

global power which depends on the need to intervene anywhere

and also needs to be able to get its population to support

massive military expenditure such a country is going to

support a nuclear strategy.

What can small nations

do?

The peace movement in New Zealand seemed to

lose momentum after the country passed the nuclear free

legislation and the US kicked us out of ANZUS. Is there more

that we can do?

There’s no question. Small

countries, like, say, Sweden, who have been out of alliance

for a long time have been able, when they wanted to, to play

a pretty constructive role in some areas. The nuclear issue

is an issue, and it’s a serious one, but it’s not the one

that really affects people’s lives. I mean, the people of

East Timor aren’t being attacked by nuclear

weapons.

They’re being wiped out by conventional

weapons, just to pick something close by. Or, say, Nigeria

and the Philippines, where there’s a lot of atrocities going

on. You don’t have to look very far away to see the use of

state violence, either domestically or across borders, which

is extremely ugly.

And New Zealand can play a

constructive role there as an independent country, just like

Sweden sometimes does. So, for example, and it doesn’t even

have to be local. I mean, the United States is, let’s take

U.S. policy in Central America, which is extremely

ugly.

I mean, several hundred thousand people have

been slaughtered there in the last decade, which is not a

small thing, and countries have been ruined to the point

where they may not survive. Now, I mentioned the Soviet

deterrent, but Europe, and countries like, say, Sweden, have

also provided a deterrent. They have been able, at some

level, to support constructive development programmes, which

gives a certain margin of survival for groups that are

trying to resist the U.S. plan for the region, which is

essentially just subordinated to U.S. needs.

Those are

factors that can’t be overlooked. The United States is a

dominant world power, but it’s not a truly hegemonic world

power. It may have been around 1950; it certainly isn’t

anymore.

It’s first among many now, and that means

that other countries, either by symbolic action or by

economic support or by public positions, can have an

influence. I mean, after all, internally, the United States

is quite free. Comparatively speaking, the citizen of the

United States is quite free from state coercion and

power.

There isn’t much that the government can do to

you, comparatively speaking. And that means that the public

opinion can make a big difference if it can get organised

and mobilised, and support from the outside is often very

helpful in developing alternatives.

Is there a risk

of US intervention for countries like New Zealand in

speaking out forcibly against its policies or do you think

that they would keep their hands off Anglo-Saxon western

types?

You know, I think there’s good reason to

believe that something pretty shady took place in Australia

with the overthrow of the Whitlam government, and

Australia’s a pretty big country.

It’s not a

third-world country. The details of that, as far as I know,

are still somewhat obscure, but there’s plenty of grounds

for suspicion about CIA involvement and external

involvement, both from Britain and the United

States.

But it’s not just that. I mean, there’s also

economic reprisals. The U.S., again, has a dominant, if not

always decisive, role in international law and international

economic institutions.

Just the fact that the United

States has such a huge market gives it enormous power over

other countries. I mean, closing off the U.S. market, for

example, can wipe out many countries in the world. That’s

the main thing that happened in Nicaragua. Much more

significant than the Contras was closing off the U.S.

market.

That’s a way of strangling a small country.

Those are all risks that are taken by anyone who pursues an

independent authority.

So, it’s just being aware

of the risks and navigating those?

I think it’s a

matter of finding other alliances. I mean, for example, the

world is really splitting up into a number of different

blocs, and that kind of competition leaves all kinds of

options open. I mean, with Europe moving towards

unification, there’s going to be a kind of a German-based

bloc, which is not insignificant.

In scale, it’s

comparable to, even bigger than the United States. It can

get its act together to major force in world affairs. The

Japan-centred Yen bloc is a major power bloc.

The

United States, in fact, is trying to construct its own bloc.

That’s part of incorporating Canada into the Free Trade

Agreement.

The Caribbean Basin Initiative is an

attempt to incorporate whatever is viable in that region

into a U.S.-dominated system, comparable to the system that

Japan has developed in its periphery. And at least these

three major economic blocs are going to be competitive,

already are competitive, will be even more so. They’ll all

be trying to get their fingers into the Soviet system, which

is just basically a third-world area that they’d like to be

able to exploit to send capital to and get resources from

and so on.

And in that kind of a complex world, the

margin for manoeuvre could be substantial.

An

Anglo-Saxon lake

General Douglas MacArthur said

the South Pacific should be managed as an Anglo-Saxon lake.

And Michael Bedford of Third World reports told me he

thought New Zealand’s anti-nuclear stance made a far

bigger impact than, say, Vanuatu’s because we’re part of

the Anglo-Saxon world. Do you think that’s

true?

Unquestionably. I mean, that’s a major

factor in policy. But it’s not just that.

I mean, just

take a look at the economies of the two countries. Sure,

there’s a racial overlap. I mean, you can discount what a

small third-world country does.

And nobody would even

know where Vanuatu is. Probably in Africa. You’d have to be

able to say it’s in Africa. Because that’s where all the

weird countries and weird names are.

Lots of people

in the US don’t know where New Zealand is for that

matter.

Former prime minister David Lange, the

man largely responsible for bringing the anti-nuclear policy

to fruition, has often said that the policy is not for

export.

Do you think other countries following

New Zealand’s or Vanuatu’s nuclear-free examples would make

the world a safer place?

I think the reduction of

nuclear weapons will. The proliferation of nuclear weapons

is extremely dangerous. The superpowers have arsenals that

are vastly beyond any conceivable strategic need and all of

that is enormously dangerous plus harmful just in getting

rid of nuclear waste and so.

David Lange argued it

was consistent to be anti-nuclea andr remain in an alliance

with the US. Do you think that’s either consistent or

desirable?

That depends very much on what the

alliance is. And if the alliance is one of defence of its

members against foreign attack. That’s quite academic. I

don’t think there’s even a remote chance of that. But if

that’s what the alliance is for, well, yes, sure, you can be

in it.

I mean if nuclear weapons do bind alliances

together, that’s a threat against their weaker members. If

the alliance is a mechanism of suppressing others, you don’t

want to be in the alliance. You should be against it. You

should try to dismantle it. If the alliance is sort of cover

for you know economic integration and so on, yes, sure, but

you don’t want to limit it to these countries. I mean,

extend it. I think one should ask what’s the alliance for?

Who’s going to attack New Zealand?

Japan’s

socialist party looks like it has a real chance of winning

an election in the future. The party has a strong

anti-nuclear policy. What do you think the US reaction would

be to Japan asserting its anti-nuclear

constitution?

My suspicion is that ways will be

found around any assertion of that policy. So, for example,

it’s been Japanese policy for decades not to allow warships

with nuclear weapons to enter Japanese ports. But although

that’s the policy, it’s never been adhered to.

I

don’ think it’s going to matter much whether it’s LDP or

the Socialist Party. I mean, Japan is basically run by a

state bureaucracy and industrial financial conglomerates.

They’re going to continue running the country whatever

politicians happen to be sitting in office.

So, you

don’t see much chance of them actually putting their foot

down and banning nuclear ships?

Not unless there’s

major popular support in the country. Something like the

revolutions that developed in the 50s and 60s there’s no

reason to expect the political bureaucracy to change the

policy.

There are anti-nuclear movements very

similar to New Zealand’s in the Philippines, Greece, Spain,

Denmark and probably elsewhere. Do you think New Zealand

should actively encourage that?

I think a kind of

a loose informal alliance among smaller powers that want to

see the threat of nuclear weapons decline is a good idea. If

they’re interested in the survival of the human species and

so on, sure, they should band together. They don’t have to

form a formal alliance.

They should communicate and be

mutually supportive and have common plans not just against

the nuclear arsenals of the superpowers but against

proliferation which is extremely dangerous. Maybe even more

dangerous.

Do you have a view on how a country

that’s decided it wants to be outside of the nuclear

umbrella should organise its armed forces. New Zealand’s

military has been designed primarily to fight in British or

later US wars overseas. We’ve fought in virtually every

war instigated by Britain or the US since the Boer

War.

I don’t think one can have a general policy

about that.

My own judgment, for example, is that

participation in the Second World War was entirely

legitimate. It was obligatory. On the other hand,

participation in the in the Indo China war was grotesque.

That was like participating in the Russian attack on

Afghanistan. So, if an alliance requires participation in

all wars, get out of

it.

…………………………….

Jeremy

Rose is a Wellington-based journalist who writes the

Substack, Towards

Democracy. Jeremy will talk to David Robie about his

book Eyes of Fire: The Last Voyage of the Rainbow

Warrior at the Aro

Valley Peace Talks, Nagasaki Day, Saturday 9 August,

2025.